I was recently involved, once again, in a debate about:

“Where do interfaces belong? With their clients or their implementations?”.

Searching the Internet for the same question displays many results and presents different opinions about the topic. In many cases, the answer is the usual one: “It depends!”. I will try to present “my” personal view about the topic. Of course, my view is not unbiased; I am certainly influenced by the suggestions of many experts in the field, but my personal work on projects comes to solidify this opinion.

In short, I could separate the interfaces in two categories:

- Consumer interfaces

- Provider interfaces

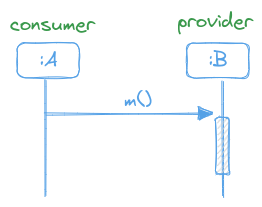

Let me first clarify what I mean by consumer and provider. When an object of class A calls a method m of a class B, then A is the consumer and B is the provider. The consumer A requests a service (requested as a method call m()) by the provider B who provides an implementation for the method m.

Consumer interfaces are the ones which are required and mandated by the consumer classes. In these cases, the consumers are the ones who describe in these interfaces their needs and define the contract for any provider class that would provide an implementation of this interface.

Provider interfaces are the ones which are defined by the providers without any specific client in mind. They usually fall into the category of general purpose libraries, like the Java Collection library, that provides both interfaces and concrete classes for all types of collection data structures.

So my short answer to the question would be:

If you are developing an application for a specific domain problem, and not a general purpose library, more often than not, you will be defining and using consumer interfaces. In that case, it is recommended that you place the interfaces together with their clients (consumers)!

In the rest of the post, I will explain why it is better to place the interfaces together with their clients, in the case of consumer interfaces.

If you are familiar with the concept of Dependency Inversion, you could skip directly to the section Modules.

Dependency inversion

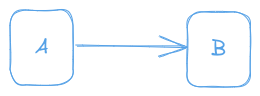

When an object of class A calls a method m of a class B, A has a dependency on B.

class A {

private B b;

public void method() {

b.m();

}

}

class B {

public void m() {...}

}

If b of class B is an attribute of class A, as in this case, the dependency is an association:

Dependencies introduce coupling. In this case, A is coupled to B. Coupling has several consequences:

- Whenever

Bchanges, there might be breaking changes to classA. AandBneed to be built together.- If we want to test class

Awe have to create objects of classB.

If it is difficult, or costly, to create object of classes B, or it is difficult to control their behaviour, then it becomes difficult to test class A. Imagine, for example, that the method m of class B is a method doing an HTTP request to an external API, or a read operation on a Database.

Generally, we don’t want abstractions of our domain to depend on details (implementations). We wish our domain classes to depend only on abstractions. As an example, you could imagine that, class A is a Customer class (a domain concept), method m is a getBalance methods that reads the balance of the customer from a database, and class B is a CustomerDB class (an implementation detail) that provides the getBalance functionality.

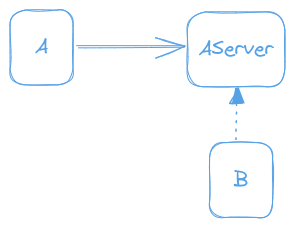

If we wish to break the dependency of A to B, we can achieve this with the introduction of an interface AServer that offers the method m. An interface introduces the desired abstraction on which our domain class A can depend on.

interface AServer {

public m();

}

Class A can now depend on the interface AServer:

class A {

private AServer server;

public void method() {

server.m();

}

}

class B implements AServer {

public void m() {...}

}

By introducing the interface AServer, our class A does not depend on the implementation of B. It depends on an abstraction.

B is an implementation of the interface AServer. A does not depend any more on B. Actually, B depends on the interface AServer that is used by A. So, in a way, the dependency is inverted (Dependency inversion).

Continuing our example with the Customer, the AServer could be a CustomerRepository interface offering the getBalance functionality of reading the balance of the customer. Within the domain, class Customer does not know (and does not need to know) if the balance is going to be fetched from a database, or from an external API. It does not need to know any implementation details. The implementation details of reading the balance are hidden within any implementation of the CustomerRepository interface. A possible implementation class B could be CustomerDB. Class Customer does not need and want a dependency on class CustomerDB!

As a result of the dependency inversion:

- it becomes easy to test the class

Aindependently of the classB. It is enough, to provide an implementation of the interfaceAServerwith itsmmethod configured in such a way that it provides the required service to classA. Bcan be easily replaced with other implementations of the interface.

Modules

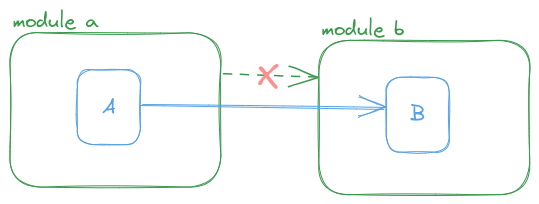

Let’s imagine that classes A and B belong to different modules. Modules, depending on the language, could be packages, namespaces, projects, etc. When class A of module apackage depends on B of module bpackage, the module apackage also depends on module bpackage:

package apackage;

import bpackage.B;

class A {

private B b;

public void method() {

b.m();

}

}

package bpackage;

class B {

public void m() {...}

}

This dependency might be an undesired dependency if class A represents a domain abstraction and class B represents an implementation detail.

If the dependency between A and B is not desired (as described in the previous section) we could invert it with the introduction of an interface AServer.

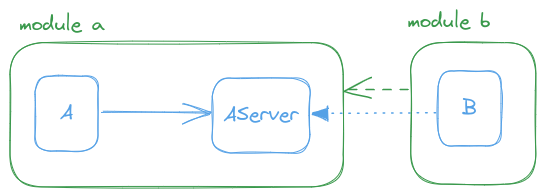

By inverting the dependency between A and B we also manage to invert the dependency between the modules; module bpackage now depends on module apackage. Module apackage knows nothing of the existence of the module bpackage:

package apackage;

interface AServer {

public void m();

}

class A {

private AServer server;

public void method() {

server.m();

}

}

package bpackage;

import apackage.AServer;

class B implements AServer {

public void m() {...}

}

Class A and the interface AServer that it uses belong together. They form a “consumer-provider contract” objects’ couple that cooperate and don’t require the knowledge or existence of the implementation class B. B becomes an implementation detail that can easily be interchanged if needed.

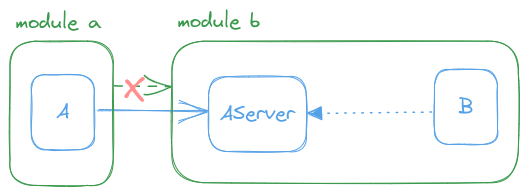

Note, that the interface AServer on which the A class depends should be in the same module with A (they belong together; A is the client of AServer). If we move the interface to module b, although the dependency between A and B has been inverted, we now have an undesired dependency of module a on module b:

package apackage;

import bpackage.AServer;

class A {

private AServer server;

public void method() {

server.m();

}

}

package bpackage;

interface AServer {

public void m();

}

class B implements AServer {

public void m() {...}

}

Keeping the interface AServer and its client A in the same module, allows module a to be developed, built, and tested independently of module b.

Unit Testing

Unit testing becomes much easier and effective, if the abstractions that we wish to test do not depend on implementation details.

For example, unit testing the class Customer becomes easy, without having to deal with details of a database.

Let’s assume that we have the following Customer class that we wish to unit test.

package domain;

interface CustomerRepository {

public long getBalance(CustomerId customerId);

}

class Customer {

private CustomerId customerId;

private CustomerRepository customerRepository;

public Customer(CustomerId customerId,

CustomerRepository customerRepository) {

this.customerId = customerId;

this.customerRepository = customerRepository;

}

public boolean hasPositiveBalance() {

return customerRepository.getBalance(customerId) > 0;

}

}

In the test, we can easily create a dummy implementation of the CustomerRepository interface, providing the arranged response of the getBalance method:

@Test

public hasPositiveBalance_Returns_true_When_balance_is_positive() {

// Arrange

CustomerRepository repository = new CustomerRepository() {

public long getBalance(CustomerId customerId) { return 1;}

}

Customer customer = new Customer(new CustomerId(99), repository);

// Act

boolean actual = customer.hasPositiveBalance();

// Assert

assertTrue(actual);

}

This way, testing the Customer class is easy. There is no need to create a complex CustomerDB class, which will require connection to a (test) database, making SQL queries, etc.

Conclusions

There are certainly cases in which the interface should be placed in the same module with its implementations (providers). I strongly believe, however, that in the majority of the cases you would be on the safe side, if you place your interface in the same module with its consumer. Most of the times, you would be developing an application in which the interfaces are going to be consumer interfaces. Only in the case that you are creating a general purpose library, in which case, you don’t know who are your clients, you will be placing the interfaces at the provider site, together with their implementations.